Commercial real estate slow to complete Libor transition

Infographic: Key questions when assessing an Alternative Investment Funds (AIFs) creditworthiness

Perspectives from China: Chinese M&A in 2022

Headwinds slow global M&A in Q2’22

New Corporate Realities: The Next Generation of Managing Risk and Operations

The U.S. commercial real estate industry still needs to transition a significant number of loans tied to the soon-expiring London interbank offered rate to regulators’ recommended alternative, the secured overnight financing rate, even though the deadline is less than a year away.

Industry experts say that many lenders have approached borrowers to amend loans and include fallback provisions so that Libor loans will automatically transition to Sofr by the phaseout deadline of June 30, 2023.

But for some Libor loans, the transition still has not been addressed. Overall market volatility and industry staffing levels, against a backdrop of surging commercial real estate transactions, have likely forced borrowers and lenders to focus on other activities, Chatham Financial Corp. Managing Director Rob Mangrelli said.

“Right now, I just don’t think there’s time and capacity to make a concerted effort in every case to kind of remediate some of the backlog issues,” Mangrelli said.

What is Libor?

Libor is a floating global benchmark interest rate used for the pricing of loans and derivative products. It is created using reference interest rates submitted by participating banks.

Formally launched in 1986 by the British Bankers’ Association, Libor served as a key benchmark for decades. That began to change in the late 2000s, when regulators started investigating claims of interest rate manipulation. Bankers at several major financial institutions were found to have submitted artificially low or high interest rates, manipulating Libor for the benefit of their institutions.

Following the scandal, Britain’s Financial Conduct Authority announced plans to begin phasing out Libor in July 2017. U.S. financial institutions stopped using Libor for new loans at the end of 2021, and the benchmark will be completely retired June 30, 2023.

No rush to transition

Outstanding U.S. business and consumer Libor loans accounted for about $6.2 trillion at the end of 2020, according to the most recent analysis by the Alternative Reference Rates Committee. Of those loans, $3.2 trillion is set to mature after June 30, 2023. Though there is no publicly available number regarding the volume of loans yet to transition to Sofr, experts say it is significant.

Many commercial real estate borrowers and lenders have contractual agreements to automatically replace Libor by the deadline, so there is no need for them to initiate an early transition, said Rachel Vinson, president of CBRE Group Inc.‘s Debt and Structured Finance business in the U.S.

“We are not seeing the urgency to transition Libor loans to Sofr that was initially anticipated. We expect to see the rate of transition increase in 2023 as we move toward the June 30, 2023, deadline,” Vinson said.

Most Libor loans are relatively short term in nature — about three years — and it could also be the case that many lenders expect Libor borrowers to have paid their loans off before the deadline, according to Cozen O’Connor’s Real Estate Finance co-Chair Zachary Samton. He added that most lenders are unlikely to leave conversions to the last minute.

“I think they’re going to have to converge, at the latest, probably in the first quarter of 2023. Because as Libor gets closer to the end and less people, less companies [and] less loans are using Libor, then it becomes less and less reliable,” Samton said.

The interest rate ripple effect

Most Libor and Sofr borrowers are required by lenders to have some kind of interest rate protection. Vinson noted that from a commercial real estate perspective, interest rate cap products have become more expensive, primarily due to volatility in the forward curve.

“When the cost of caps increase, especially to the extent we’ve seen over the last few months, greater equity is then required, as the cost of the deal increases. For some CRE borrowers, this dynamic will likely force a capital markets transaction,” Vinson said.

Higher-than-expected interest rate caps can derail the economics of a deal and cause problems during the closing process, according to Samton. There has also been a reduction in the number of companies willing to provide interest rate caps for Sofr loans, compared with Libor loans of the past, Samton added.

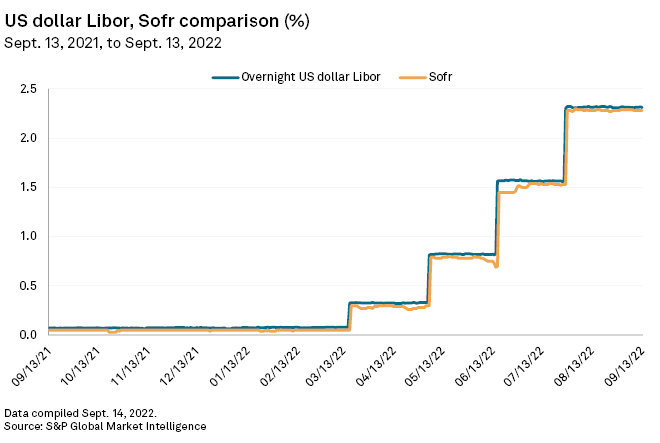

Recent increases in Libor rates have made Sofr a cheaper alternative for borrowers. But the rising interest rate environment has even prompted commercial real estate borrowers to shift away from floating rate loans, like Libor and Sofr, into fixed rate products, Vinson said.

“With the inversion of the yield curve, borrowers are choosing to hit the pause button on locking in permanent financing and are instead opting for short-term bridge and/or [mezzanine] structures,” Vinson said.

Experts agreed that, despite the slow pace to date, the transition from Libor to Sofr has been much smoother than expected.

“I’m more worried about rising interest rates than I am about the transition from Libor to Sofr. Libor to Sofr has been smoother than most of us thought it was going to be,” Samton said.